14 siders intervju i magasinet Fotografi

Et av mine verk er på magasinets forside og på innsiden et intervju, portrett og mine fotografier over hele 14 sider. De siste månedene har jeg hatt fint besøk av Katinka Goldberg, som har gjort intervjuet. Hun og vår sibirkatt Lola fant fort tonen. Fotografi Bjørn Wad og redaktør Pål Otnes kom til mitt studio i skogen og til mitt hjem for å filme og portrettere meg til magasinet. Resultatet finner dere i nyeste Fotografi, som ble lansert forrige uke med samtale mellom Andrea Gjestvang og meg i Oslo, ledet av Preus Museums kurator Hege Oulie. Jeg synes det har blitt veldig fint, og er takknemlig for alle de fine menneskemøtene som kom ut av denne prosessen. Verket på forsiden har dere mulighet til å se utstilt i Gyldenpris Kunsthall i Bergen i slutten av mai og hele juni.

Interview is written by Katinka Goldberg

The portrait of me is taken by Bjørn Wad

IN ENGLISH:

SORROW THAT IS NOT FELT

Interview by Katinka Goldberg in Magasinet Fotografi

The snow lies in great drifts as we come up the driveway to Marie Sjøvold’s house, and both of us are surprised that the cat wants to be out in the winter cold. I am visiting the Sjøvold family’s cosy, messy house with floral wallpapers to talk about Marie’s new book, her relationship with photography and her many upcoming exhibitions. For it’s an intense spring and summer that’s in wait for Marie Sjøvold, who despite her 40 years of age has been a significant figure in Norwegian photography for many years.

In April Marie will travel to France to open an exhibition at Musee de Beaux-Arts in Rouen, in May she has a solo exhibition at Gyldenpris Kunsthall in Bergen, in August she has another exhibition at Fotografisk Center in Copenhagen, and in September she and Charlotte Thiis-Evensen show their travelling exhibition at Hå Gamle Prestegard in Stavanger.

But on this day Marie sits in her sofa and looks into a moment of winter sun. She is careful but insistent in the way she talks about her pictures. Marie has an unmistakable drive to capture her experience of the world in pictures. At the same time she consistently shows a tenderness – towards the people she depicts and to the medium of photography itself. Marie uses photography as well as video installations, photo books and sculptures to describe changes and transitions in life – motherhood, pregnancy and the unpredictable country between being asleep and awake – in short what it means to be human.

SILENCE AND NOISE

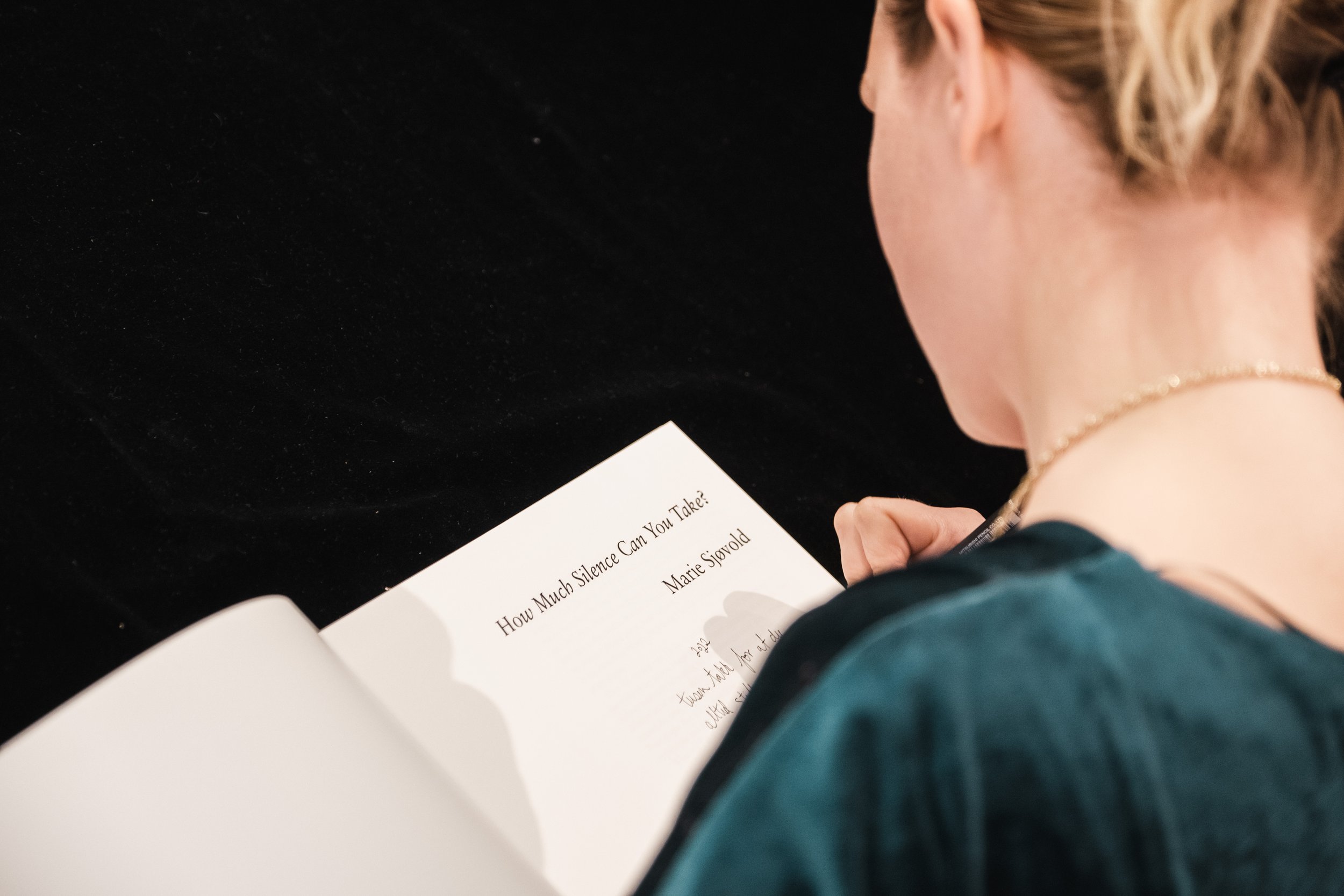

In her latest photo book project How Much Silence Can You Take? she explores silence, or maybe our need to escape from it. The book was published by the Swedish publisher Journal last autumn and is about our relationship with social media. The project is an act of resistance against the zeitgeist. A political stance created by a personal point of view. Marie has taken a one year break from social media to see what it does to her and her way of seeing the world. Instead of pulling out her phone she has picked up her camera. The pictures are unmistakably Sjøvoldian but they have a hint of melancholy – a sorrow that is not felt. The narrative is open, and the book is more like a piece of music than a visual story. She herself describes it as a different kind of openness in the pictures, because she chose a more intuitive approach in the method of her photography.

With this project I found a different photographic eye. It turned out that I took pictures in all the situations where nothing was happening. When you are just waiting. Later, when working on the book, my publisher Gösta and I decided to immerse ourselves in that silence.

This is the third book Marie publishes with Journal. The publisher Gösta Flemming shares Marie’s interest in the tactile and has a deep knowledge of how the choice of material elevates the story. Together they make books that challenge the very format as well as make it possible for Marie to create an image world that envelops the viewer.

THE TACTILE PHOTOGRAPH

When I look at Marie’s pictures I think of photography’s unique ability to hold the world in place. That past life is no longer just an unpredictable memory, but captured forever. It has become its own story that lives on alongside the memory or the experience. An encapsulated promise of being there to us, the viewers. Roland Barthes describes it as a kind of umbilical cord which connects the captured subject to our gaze, even if we can’t touch it the light becomes a material element, a skin we share with the one that was photographed.

To Marie Sjøvold the bodily element of photography is a reality that shapes the entire creative process. One example of this is the insistence on presenting photography as an object with physical presence in the room.

Much of the process in a photographic project is based on immersion and thought. But I also work with photography in a more bodily way. Both during shooting and selecting pictures as well as in the design of the exhibition space.

In her latest project How Much Silence Can You Take? she places crumpled large format papers directly on the floor, or on a low pedestal. Photo paper that feels like velvet but is wrinkled like old skin. It is at once beautiful and uncomfortable, while it also comments on the fleeting nature of memory due to its form.

The sculptures are an attempt to see how far away I can get from photography while still being able to define them as photos. It stems from the restriction to the two-dimensional, flat photo. A desire to liberate myself. To enhance the sensual, physical experience of a photo.

We take a break from the interviewing and Marie goes to make tea in the kitchen. In the short silence that arises I suddenly see Marie Sjøvold pictures everywhere. A wilting houseplant’s silhouette against a milky-white window, even the cat as it lies on the coffee table with its sand-coloured, somewhat ruffled fur, are all parts of her colour landscape. After an hour of interviewing, her way of seeing has inched a little closer.

MOVEMENT AS INSPIRATION

I ask Marie about artists who inspire her, and one she mentions is the German choreographer and dancer Pina Bausch. And now it feels like the pieces are falling into place for me. I may be biased given my own great interest in dance, but I don’t think so. I think it’s because this opens her artistry to me. I immediately see things I didn’t before: the awareness Marie has of how she lets the figures move in the picture space. Their sensuous, rhythmic relation to the landscape around them. It also interests me that Marie thinks of art forms completely different from photography as inspiration, which she also points out herself.

I find inspiration reading photo books, but more and more I look at other media than photography. It is said that you shouldn’t drink from the same well for friendship and love, and I think that holds true for photography as well. In order to evolve photography it is fine to look in completely different directions. Pina Bausch had a holistic view of what art and life is, that dance and life are as one – and I actually think that’s how I like it too. That creativity and daily life flow together in one great whole.

PHOTOGRAPHY AND PRESENCE

I wonder if the very narrative about what happened is what’s the important thing, the big thing, if that’s what lets you get really close to life? Especially in Marie’s latest book it’s as if she claims that a photo can also be a state of being – which in turn generates a new presence. When I listen to Marie I realize that for her, photography is a way of getting closer to life.

Through the camera I experience everything more concentrated: I feel that I can be even more intensely immersed in the material. With the camera I can sharpen my presence and my consciousness.

Maybe it’s just about longing? Longing to tell stories and get close to each other. To hold on and to expand. To be able to lie in the grass among blue flowers and get ants in your hair and be held. When we see Marie’s pictures we are reminded that it’s possible to be in a moment of happiness. Photography as an opening into existence.